Africa still has vast regions which are ornithologically undocumented and may offer surprises and potentially new discoveries. This is certainly true of Mozambique: a country with low population density and poorly explored wetlands, lakes, woodlands and forests. Even as a frequent visitor to this exciting country, one is never quite sure what to expect!

The story of Forbes-Watson’s Swift in Mozambique begins in March 2017, when I led a birding tour to southern Mozambique – a trip which produced a nice collection of regional rarities, including Basra Reed-warbler Acrocephalus griseldis and River Warbler Locustella fluviatilis. Based on the coast, north of Vilanculos, we had set off early to the Save Forest, some two hours away, and arrived just after sunrise in an area of partly disturbed forest and mixed woodland. The effects of pirate loggers are still visible – yet it retains a feeling of true wilderness and the birding can be excellent. With regional specialties, such as Livingstone’s Flycatcher Erythrocercus livingstonei and Neergaard’s Sunbird Cinnyris neergaardi on offer, the birding was good! We compiled a species list for the Southern African Bird Atlas project, recording all of the species seen on a smartphone app: BirdLasser. At around 10:00 a flock of large, dark swifts were detected overhead and after a quick look we concluded that they could only be Common Swift Apus apus. However, a short while later it became apparent that the swifts were screaming – something that I can’t ever recall observing in Common Swift on its wintering grounds. I thought this was odd – but more urgent birding called, and we moved on to find the Eastern Green Tinkerbird Pogoniulus simplex – a species only recently rediscovered here and thus a priority for birders in Southern Africa.

The deck of the Lodge at Inhassorro where the Swifts were seen.

In the afternoon, we returned to the coastal village of Inhassoro. As sunset approached, I found myself birding on the deck in front of the lodge which overlooks a quiet section of the Indian Ocean between the Mozambique mainland and the Bazaruto Archipelago. Not much was about except for a flock of Common Swifts, wheeling about in the sky above. But hang on – the swifts are calling! What’s going on here? Through binoculars these birds looked a little pale – perhaps the pekinensis race of Common Swift? Another odd feature: I had never noticed such a prominent white throat patch on Common Swift before. Furthermore, the calls and even the behavior seemed strange. With the birds now disappearing out over the ocean in a lazy wheeling motion, I decided to grab a sound recording with a handheld voice recorder I carry in my shirt pocket. And I am so very glad I did, although it would take three years to solve that afternoon’s mystery.

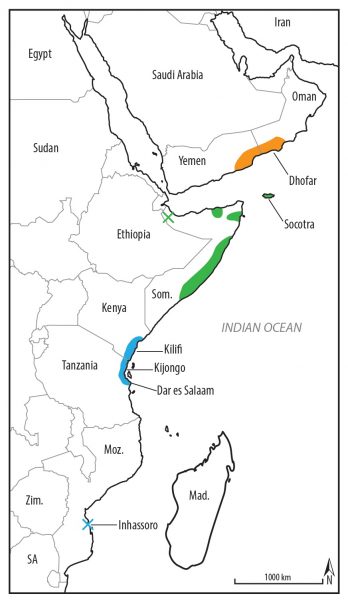

On intense birding tours in Africa, there are so many questions one never gets around to following up. And so, the odd swifts and the recording I had made receded into ancient history with many subsequent visits to Mozambique. Then, in 2020 the covid pandemic was upon us and birding travels were suddenly and catastrophically halted. The world locked down and I found myself stuck at home instead of flying to Namibia for a wonderful birding tour! Gary Allport shares my passion for Mozambique and in late March we happened to be talking about overshooting snipes, errant warblers and other exciting possibilities which might be added to the Mozambique List. Gary recalled a discussion with Neil Baker about a swift he had photographed earlier that year. Neil suggested that Forbes-Watson’s Swift Apus berliozi might migrate further south than we currently suspect. Forbes-Watson’s Swift, which breeds around the horn of Africa, on the island of Socotra, and in southern Arabia, is known to winter on the Kenyan coast. There are also recent scattered records in Tanzania, but these are too few and far between to really establish a solid pattern. This poorly known swift had certainly never entered my mind as a possibility for Southern Africa.

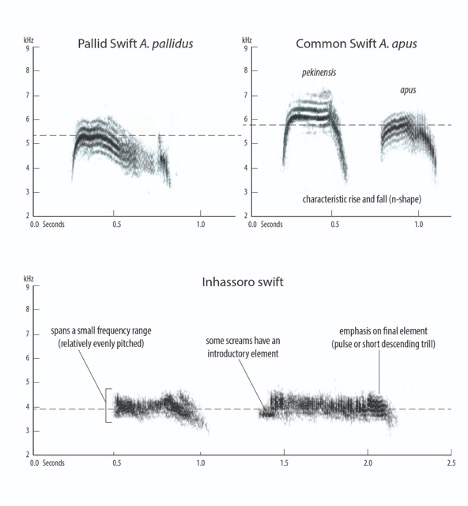

Comparative sonograms of the ‘Inhassoro swift’, Apus apus and Apus pallidus

That unresolved swift observation from three years prior came back to mind and I asked myself what if? A rather frantic search of my back-up hard drives for old sound recordings ensued. After some detective work, I pinned down the date and found a single 40 second clip on the correct date. And yes – in amongst the noise from the wind and ocean, one could hear swifts calling! Comparing it to recordings of Forbes-Watson’s Swift on Xeno-Canto was tantalizing to say the least! I shared the file with author and illustrator Faansie Peacock, while Gary Allport sent it on to Guy Kirwan and Brian Finch in East Africa. We all thought that the recording sounded closest to Forbes-Watson’s, although southern Mozambique would be a 1 700 km extension of its wintering range.

The only way to answer these questions was to take a deep dive into the vocalizations of swifts. Thus it was that three years after the Inhassoro sighting, Gary Allport, Faansie Peacock and myself set out to analyze the sound recording and compare it to similar swifts’ calls. We drew initially on the important work of Grieve and Kirwan (2012), in which they used sonogram analysis, and comparison with other swift species known or likely to occur in southern Arabia, to demonstrate that the screaming calls of Forbes-Watsons Swift are sufficiently distinct to allow species-level identification.

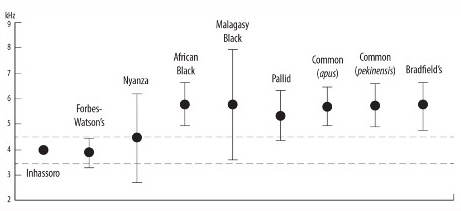

Comparison of the mean frequency at peak amplitude of ‘Inhassoro swifts’ with the seven taxa analysed.

Using a similar approach, we analyzed the screams of all seven species of large, dark swifts that might occur in southern Mozambique. Both subspecies of Common Swift were analyzed separately and we cast the net wide by including Bradfield’s Swift A. bradfieldi, which is endemic to the arid western half of southern Africa. Overall, we used 21 recordings of the nine taxa (including the mystery ’Inhassoro swift‘). Individual flight calls were analyzed and measured separately to create a comparative dataset comprising 276 individual flight calls for statistical analysis. In comparison with other taxa, the mean frequency at maximum amplitude of the ‘Inhassoro swift’ did not differ significantly from that of Forbes-Watson’s Swift, while t-tests showed significant differences in the flight screams of all the other taxa.

Distribution of Forbes-Watson’s Swift A. berliozi showing breeding range in Somalia (‘Som”) and Socotra (green), southern Arabia (orange), and non-breeding range in coastal southern Kenya and northern Tanzania (blue). The location of the observation described in this article (Inhassoro, Mozambique) is indicated with a blue ‘X’.

The screams of all the taxa were also assessed both visually on the sonograms and aurally at normal playback speed as well as at reduced speed – the latter aiding characterisation of the rapid, complex screaming calls. Although the screams of these swifts sound rather similar to human ears, we were able to show that they are indeed distinctive in terms of structure and measurable characteristics.

A little late perhaps, but this represents the first record of Forbes-Watson’s Swift for Mozambique and for the southern African region. This record extends the non-breeding range dramatically further south. Is Forbes-Watson’s Swift a regular migrant to the region? Birders should certainly be on the lookout for this species, and we strongly advocate recording the screams of any interesting-looking swifts in the region. Field identification remains a challenge and with the aid of excellent plates by Faansie Peacock we provide several pointers that will aid birders in identification of this taxon in the hope that more can be learned about its occurrence in south-eastern Africa (See Marais et al, Bull. B.O.C. 2021 141(1): p33.