Flamingos are one of the most popular bird groups in the occidental pop media and the public imagination. Their exquisite features attract attention wherever they are, but there are still many things to learn about these magnificent birds. Amongst them are their long-distance movement patterns. While the six flamingo species have frequently been considered to be migratory, relatively little is known about their long-distance movements, especially in the case of the South American flamingos.

Our first doubts about the migratory status and movement behaviours of flamingos started in the field. Our project, the “Flamingos do Sul”, has studied the behaviours and ecology of Chilean Flamingos since 2019, at an important wetland in southern Brazil: the Lagoa do Peixe National Park. If Chilean Flamingos were migratory, we would expect them to use the lagoon to rest and feed during the Austral winter and leave the area at the very beginning of spring, returning only at the end of autumn the next year. But that was not the case: in some years, groups of nearly 200 flamingos stayed in the lagoon during November, while in others only four birds were reported in the same month.

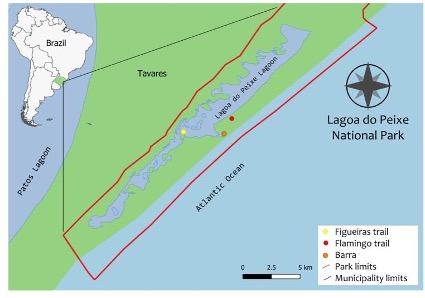

Figure 1. The Lagoa do Peixe National Park is one of the most important wetlands in Southern Brazil, and is home to the Brazilian population of Chilean Flamingos and the only place where this species can be seen all year round. The map shows the limits of the park and the main areas where flamingos can be found. Map by Oscar M. Aldana-Ardila.

Another observation that caught our attention was the age of Chilean Flamingos in the Lagoa do Peixe: during some months, adult individuals formed the majority, whereas in others only juveniles were present. It seems that these Chilean Flamingos not only exhibit high spatial and temporal variation in their movements to-and-from the Lagoa do Peixe National Park, but also intraspecific variation, influenced by population and individual characteristics, such as the age or stage of the reproductive cycle of the individual birds.

Based on these observations, we asked: Are these flamingos a strictly migratory species and how can we characterize their movements? These simple initial questions led on to more difficult ones: What is migration? What defines a migratory species? Is every long-distance bird movement a migration? Are there other types of bird movements that are not migration? We turned to the literature for answers to investigate the various definitions and empirical data and to review other studies of flamingo movements that could shed light on the behavior of these species.

Different movements for different birds

Birds show different types of movement that can be divided into three major groups: movements inside their home-range, on a daily basis, in search of food, water or partners; movements that extend the home-range, when needed, to explore new areas to find resources; and the long-distance movements that we usually call migration. Migration is defined by a set of unique characteristics: it comprises regular, long-distance movements that occur seasonally, with fidelity between sites along the route, and is related to physiological changes in the bird. It is usually related to population patterns and linked directly with the breeding season and climatic changes during the year.

Nevertheless, many different bird species also make long-distance flights that include some or none of these characteristics. Some birds fly long-distances without any temporal repetition or regularity, others do not show site fidelity at all, and some even travel long distances far from their original goal by mistake, due to climatic adversity. The literature often sets different terms for these different kinds of movement patterns, and this can lead to confusion and mis-definition of a bird’s movements. To clarify our investigation, we used six different categories of movements based on the literature: migration sensu stricto, dispersal, irruptive, nomadic, vagrant, and sedentary.

What about flamingos?

For some years, flamingo specialists have discussed the migratory status of the six species. However, flamingos are still classified as migratory in many official documents and among the public. Some studies have already found that flamingos move through wetland areas in response to climatic conditions and resource availability, adopting very erratic movement patterns as they go. However, other studies have found that flamingos exhibit high site fidelity, especially regarding their breeding colonies, but that dispersal from these colonies is related to individual age, sex and social status, and changes from year to year.

Figure 2. Flock of Chilean Flamingos resting among other bird species in the “Barra” of the Lagoa do Peixe Lagoon. Recent studies have found that while flamingos use this area to feed and rest, the park is also important for many of their social activities. Photo by Henrique C. Delfino.

This intraspecific variation in movement patterns, influenced not only by climatic variables, but also by individual and population variables, is evident from our observations in the Lagoa do Peixe National Park: flamingos do not fit the strictly migratory pattern, but instead exhibit different behaviours that can change between both years and individuals. But, if flamingos are not true migratory birds, how can we classify their movements? Based on the literature and empirical evidence from different studies, we classified flamingos as irruptive or nomadic animals: species that make seasonal movements where the number of individuals moving, and the timing, direction, and distance travelled varies greatly between years and colonies.

Ecological classifications in relation to conservation problems

Many migratory birds are currently under threat and numerous conservation plans have been developed around the world to protect the habitats used during their lifecycle. Our idea when discussing the long-distance movement patterns of flamingos was, of course, not to exclude these birds from such management and conservation plans, but to show that these plans should be expanded to include different bird movement patterns and to include species that are not strictly migratory. This discussion of the current classification of flamingo movements is also an effort to consolidate current knowledge about these species and to show the necessity for further studies on the movements of these magnificent animals.

Author Information

Henrique C. Delfino and Caio J. Carlos

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Zoologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Laboratório de Ecologia e Sistemática de Aves e Mamíferos Marinhos (LABSMAR). Av. Bento Gonçalves, 9500. CEP: 91509-900, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. Contact emails: henriquecdelfino@gmail.com and macronectes1@yahoo.co.uk

https://www.instagram.com/flamingosdosul/

https://www.facebook.com/flamingosdosul