Carolina Parakeet from John James Audubon’s Birds of America (ca. 1827)

The Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis) was the United States’ only native parrot[i]. It occupied a remarkably wide range, from the swamps of Florida all the way to the plains of Nebraska, where it persisted even in snow and cold. The species often occurred in cypress woods in the southeast, and amidst sycamores in the midwest, and was never found far from water. With its bright green plumage and shrill, discordant calls, the birds were hard to miss, and if you saw one, you saw a whole flock.

Since its extinction in the first half of the twentieth century, Carolina Parakeets are only found in a museum or in our imaginations. If we are willing to trek into the strange country of the past, we can discover details that no museum skin can share and for a moment experience the lost beauty of this species.

Any quest for the Carolina Parakeet starts with Daniel McKinley, the parakeet’s most dedicated researcher. He reported parakeet records throughout its range in more than 25 articles over almost 30 years. McKinley uncovered over 400 historical records of the parakeet, all without the use of the internet; he simply read every historical diary he could. Using modern research tools, I resumed his quest for Carolina Parakeet records.

I quickly learned that early Americans were eccentric spellers. Searching for “parakeets” produced almost no new results. However, I soon discovered that “paroquets” was the preferred spelling before 1900, and its various (mis)spellings yielded far better results. But the past can quickly lead you astray. “Paroquets” sometimes referred to puffins; “parrots” were a type of artillery used in the American Civil War; and the French spelling “perroquet” is also the name of a special mast on a ship.

Searching for “paroquets” with “cypress” or “swamp” yielded good results, as did searching for parakeets alongside Northern Mockingbirds (Mimus polyglottos). Apparently, many northern authors visiting the south saw both the parakeet and the mockingbird as emblematic of the south. For instance, Philip Paxton wrote from Texas of parakeets along with Ivory-billed Woodpeckers (Campephilus principalis) and mockingbirds:

Birds of showy plumage and joyous voice – the dandy paroquet – the log cock with

his gaudy head dress – the dusky mocking-bird whose imitative but inimitable song

more than compensates for his Quaker attire were flitting to and fro…

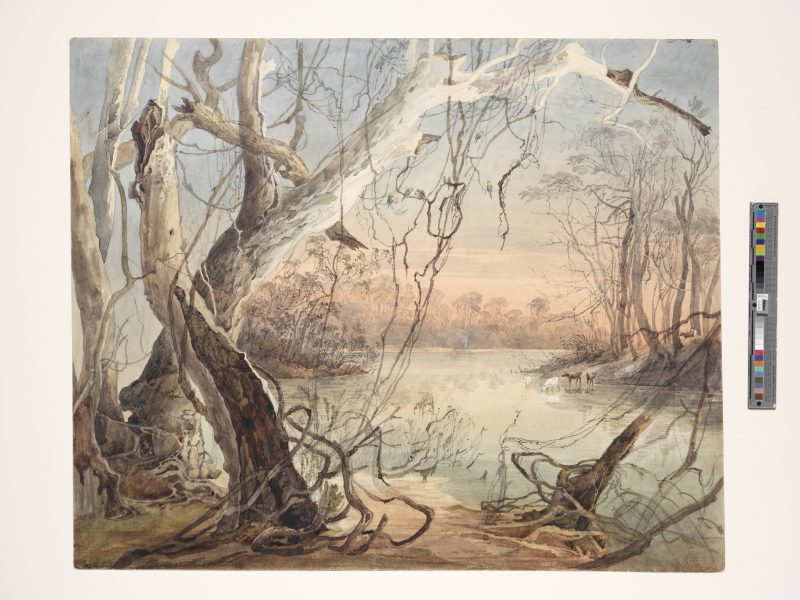

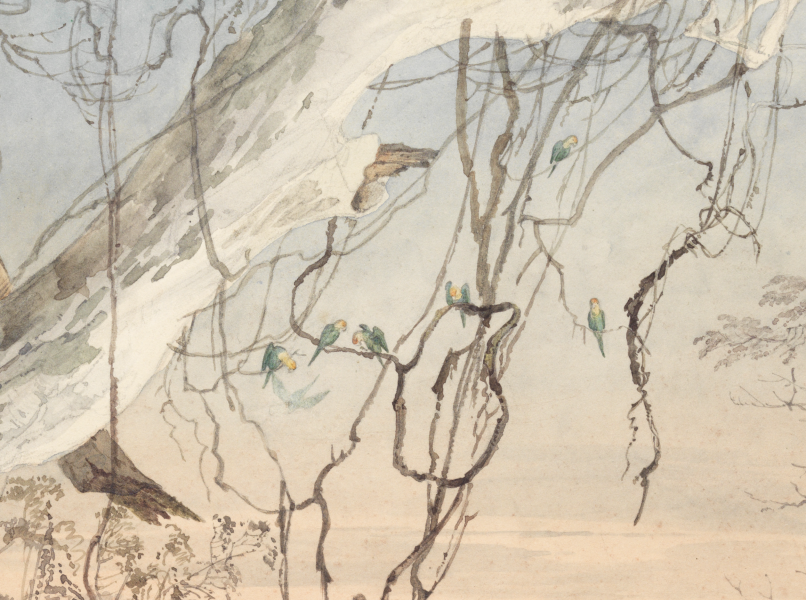

My search for the species along the Missouri, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers focused on the people who were moving and living along these rivers and their tributaries. Prince Maximilian zu Wied saw parakeets during his winter stay at New Harmony, Indiana in 1832-1833 (Karl Bodmer, the artist of Maximilian’s expedition painted this image while there).

Both images above: Karl Bodmer (Swiss, 1809–1893), Confluence of the Fox River and the Wabash, 1832, (detail above) watercolor and graphite on paper, 11 15/16 × 14 5/8 in. (30.3 × 37.1 cm), Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, Gift of the Enron Art Foundation, 1986.49.63, Photograph © Bruce M. White, 2019.

The famous pioneer, Daniel Boone, shot a parakeet near his final home in St. Charles County, Missouri. Hundreds of thousands more people became potential parakeet observers as they walked along the Missouri River, seeking gold or land or freedom in the west. Searching on the names of trails, like the Oregon and California, along with the goals of those trails like “gold rush” yielded more parakeet records. For instance, Elisha Perkins travelled west in the 1849 Gold Rush and was “much surprised by a flock of genuine Carolina paroquets fluttering and chattering through the woods” in the St. Joseph area, Missouri.

The Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) moved west seeking freedom from religious persecution. One such migrant, Thomas Bullock, recorded one of the westernmost records of the Carolina Parakeet on 27 May 1847:

I saw two Parrots or Parroquets-planted a hill of corn at this place-another Barren

road; plenty of Prickley Pear-rained[.] 13 ¾ [miles]

Bullock planted corn in the hope that it would grow and be harvested by other Mormons making their way to Salt Lake City. It was in the midst of daily life, sometimes at home but more often on the road, that people encountered the parakeet, and noted it as part of their story.

In my recent article in the BBOC, my co-authors and I reported 131 additional records of the Carolina Parakeet. Many observers I encountered were part of the history of the United States, such as:

- Anne Royall, perhaps the USA’s first female journalist

- John Landreth searching for wood for the navy

- Eliza Farnham, an abolitionist and prison reformer

- Bishop Francis Asbury of the Methodist Church

- Esther Hawk and Charles Brackett, both doctors during the American Civil War

- Revd John Bachman, one of Audubon’s dear friends

- Alice Robertson, the second woman elected to the United States Congress

Since finishing my BBOC manuscript, I have found even more records of the species. And I am going to keep pursuing parakeets in the past to be sure that their story remains part of our story.

Ben Leese spends his days in a microbiology lab, but loves studying the Carolina Parakeet and other extinct species. He enjoys working in his garden, especially his native meadow, and likes spending summer evenings cheering for nearby minor league baseball teams.

[i] Except for a small portion of the Thick-billed Parrot’s range in Arizona.