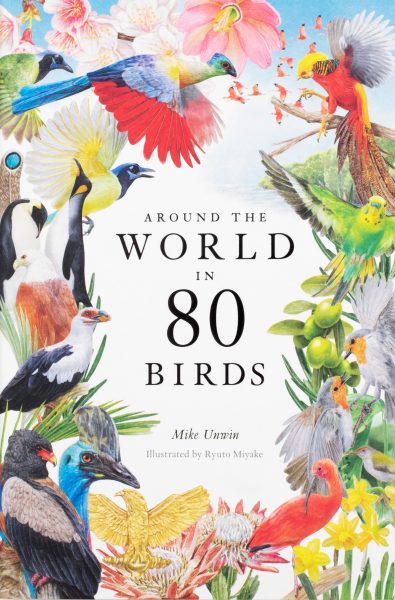

An interview with Mike Unwin on this latest book ‘Around the World in 80 Birds’. The book is illustrated by Ryuto Miyake and published by Laurence King.

Reproduced with permission from the Quarterly Newsletter (Issue No. 270, September 2023) of the London Natural History Society.

Mike Unwin is an award-winning writer of popular natural history books for adults and children. He writes for The Daily Telegraph, The Times, BBC Wildlife, Travel Africa, as well as the RSPB and WWF. Also a widely published photographer, his travels have taken him to every continent in search of its birds and other wildlife.

How did this book come about?

My book is the latest title in Laurence King’s award-winning Around the World series, which explores our relationship with the natural world through a collection of species ‘biographies’, each representing a different country or location. Birds were a natural subject for this series, given their huge variety and the great impact they have made on history and culture. My 80 biographies describe the natural history of each species and account for its significance in its particular part of the world. Collectively, they also illustrate the breadth of the bird world and reveal how integral birds have been to our history and culture worldwide.

How many years was this book in the making?

I started writing this book early in 2020, and the final stages – including Ryuto Miyake’s gorgeous illustrations – were completed late in 2021, ready for publication in May 2022. The entire process thus took place during the Covid 19 pandemic. This timing was significant: the enforced confinement of lockdown, with its empty skies and quiet streets, prompted many people to pay more attention to birds, becoming more curious about their lives and more grateful for the ways in which they enrich our own. My awareness of this rekindled national interest gave extra impetus to my writing.

What do you want to achieve with this book?

I hope that my book will convey the importance of birds, not only in terms of their natural history but also in terms of their value to us. My selection of species aims to illustrate the huge variety of ways in which humankind worldwide has related to birds over the course of history. Many have symbolic qualities, their colourful plumage, predatory prowess, nest-building skills, mesmerising voices or powers of flight elevating them into icons of art, literature, music, folklore and religion – from Keats’ nightingale to the quetzal of the Aztecs. Others have offered us more practical resources, from food and feathers to navigation aids for sailors. Meanwhile, birds provide us with vital services, from pest-control to mental health, and the study of birds has also enriched our understanding of science, including evolution itself. I hope the reader of my book comes away believing that all birds are remarkable – not only the ‘A-list’ species, such as emperor penguin and Andean condor, but also the lesser-known, such as the greater honeyguide, which enjoys a mutualistic relationship with honey-gatherers based on its ability to locate bees’ nests, or the common swift, which can remain on the wing for an astonishing 18 months without touching down once. Underlying all this, I hope to impress upon the reader how threatened birds are by the impact we are having upon them and their environment – and just how much we stand to lose, if we lose them.

Is there a fun fact or something amazing you learnt during the writing of the book?

I thought I was reasonably familiar with the species I selected, but my research brought many revelations. My favourite, perhaps, is the story of the white stork that appeared in the German village of Klutz in 1822 with an arrow through its neck. The arrow turned out to be of African origin – thus providing definitive proof, long before the advent of ringing, that birds migrated between Africa and Europe.

Were there any memorable moments during the course of writing this book?

I can think of nothing exceptional during the writing process itself – although the mellifluous song of a blackbird outside my office window during that first lockdown spring provided a daily stab of guilt that this species had failed to make the final list. However, the book reflects a lifetime of pursuing birds around the world and is thus, in that respect, a composite of many memorable moments. These range from meeting the berkutchi eagle hunters of Mongolia, who placed a trained golden eagle on my wrist, to communing with a solitary wandering albatross from the stern of a ship crossing the stormy Drake Passage to Antarctica. It is the measure of the impact of birds upon us that they provide an immediate reference point for anywhere I have ever visited and are inseparable from many of my most significant life experiences.