An interview with Christine Jackson on her book ‘A Newsworthy Naturalist: The Life of William Yarrell’ published in association with the British Ornithologists’ Club (BOC).

Reproduced with permission from the Quarterly Newsletter (Issue No. 266, August 2022) of the London Natural History Society.

Christine E Jackson attended Greenhead High School, a grammar school in Huddersfield and Manchester Library School leading to the qualification A.L.A. (Associate of the Library Association). She was Librarian of Mander College of Further Education, Bedford and Branch Librarian of Radlett, Hertfordshire when she published her first book, ‘British Names of Birds’ before retiring in 1970 in order to research and write on ornithology. Each of the 15 following books has broken new ground and pioneered bird illustration (wood engraving, etching and lithography) and bird art with a ‘Dictionary of Bird Artists of the World’ (4,000 entries) and 5 biographies of bird artists. A book on ‘Fish in Art’ was a further pioneering study.

How did this book come about?

‘A Newsworthy Naturalist: The Life of William Yarrell’, published in 2021 by John Beaufoy and the BOC, is, surprisingly, the first biography for this eminent naturalist of the mid-19th century. He was a successful businessman enabling him to form a large library and private museum of fish and bird and other specimens, the sale of each taking three days in 1856 when he died. He was the author of two standard works of the 19th century: ‘A History of British Fishes and ‘A History of British Birds’, both published in the 1830s with delightful wood engravings of which his friend Thomas Bewick would have been proud.

I came across his collection of letters in the Bath Royal Library and Scientific Institution, sought out all other letters I could find and either transcribed or abstracted them. They were so interesting and revealed how much his original research and anatomical studies had revealed several species that were new to science and other bird and fish species that were new to the British fauna.

Because he was such an influential figure in London among the major natural history societies, the minutes of meetings of the Zoological Society, of which he was a founder member in 1826, sometime secretary, and Vice-President, yielded information about his valued administrative qualities. He was also a Secretary and Vice-President of the Linnean Society and founder member and Treasurer of the Entomological Society. He chaired the first inaugural meeting of an Ornithological Society of St James’s in 1836 that formed in order to pay for, and put birds on, the lakes in the park. It was joined by several aristocratic members in 1837 who took over the new society and in 1837 altered its name to Ornithological Society of London. Living in Westminster all of his life, between Piccadilly and St James’s Park he was at the centre of natural history activities.

How many years was this book in the making?

It usually takes me about 4 years to research a new title, then 9-12 months to write the book. Having transcribed all of the letters I could locate over several years before starting on the biography, a search was then on to find background to his two books, relations and friendships with other naturalists, his work for the Zoological Society on its committees in particular and sources for the text of his books. Making copies of the wood engravings in his books to use for illustrations was a most enjoyable task. Yarrell had employed the most sought after wood engravers in London and the engravings are some of the best in any natural history book.

Since the genealogy of the families of Yarrell and his partner in the bookselling and newspaper business Edward Jones, (still in existence today as Jones Yarrell Hand to Hand) were unknown, a genealogical search had to be undertaken. I was used to doing this having written the history of the houses and their occupants in two villages in which I had lived.

What do you want to achieve with this book?

To give Yarrell some credit where it is due for his vast contribution to our knowledge of British fishes and birds in his standard works and to trace the new discoveries he made and reported in the society journals after his anatomical and literary researches. Among those discoveries was the difference between the Whooper Swan and a species he recognized as being new to science as well as to the British fauna which he named Bewick’s Swan in 1830. This established his reputation at the beginning of his career as a naturalist. He also found that the male sea horse kept embryos in his pouch until ready to hatch and start life independently; that birds have a tiny egg tooth to help them to chip their way out of their egg; that eels gave birth to live young, and several original other details of bird and fish life. These discoveries were reported among the 80+ periodical articles he had published.

Is there a fun fact or something amazing you learnt during the writing of the book?

The generous relationship between Yarrell and other authors, The Reverend Leonard Jenyns, Sir William Jardine and John Gould in particular, who were happy to share information was truly pleasing.

Yarrell loved entertaining and held evening parties when he would sometimes break out lustily singing current songs that he picked up on his visits to the theatres. Learning a new song he went twice, noting down lines 1, 3, 5, etc the first visit, and lines 2,4, 6 etc on the second visit. He evidently picked up the tunes (he owned 2 pianos) by ear. The amount of travelling by coach to meetings, to visit friends, to fish and collect specimens along the coasts was amazing. He had to fit all this in with his duties in the business as a co-partner, and immense amount of time he devoted to the affairs of several societies. He lived his life in three separate compartments – business, societies and authorship – and was meticulous in discharging his duties in each. His correspondence was immense, again conscientiously attended to and contributions from other naturalists acknowledged in his books.

What online resources and library resources did you use for your research?

Zoologists would find much of interest in the letters between Yarrell and other naturalists about species of birds and fishes in particular, but also insects, mammals and reptiles. They would also discover many more details about the work and characters of other famous contemporary naturalists, e.g. Edward Lear and Charles Darwin. An author of histories of the London natural history societies would soon find Yarrell a leading influential figure of the 1830s-1850.

There are over 7,000 entries under the name Yarrell in the National Newspaper Archives. Though some are other persons named Yarrell and a placename including Yarrell, the bulk of the entries are about William Yarrell.

Yarrell turned out to be far a more interesting man than I had ever envisaged and was an admirable character much loved and esteemed by his contemporaries. There were at least 40 obituaries in newspapers when he died.

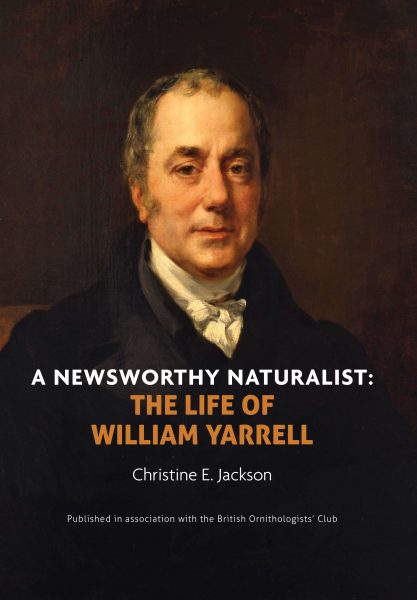

The book cover is a Portrait of William Yarrell (1784-1956) in 1839, courtesy of the Linnean Society Library.

‘The book is widely available from on-line booksellers including NHBS.