Source: Wikipedia

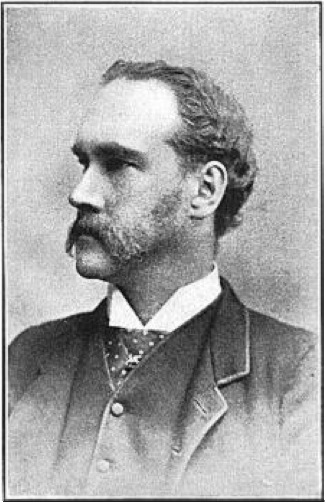

Trite, but true to say, is that Howard Saunders, the first Secretary and the first Treasurer of the Club, was born in 1835 in London into a very different world. Dickens was writing the Pickwick Papers and King William IV was on the throne. Saunders’ business role as a merchant banker saw him travelling widely. From 1855 to 1862 it took him to Brazil and Chile. He studied the birds of Spain and Italy during the later 1860s and his first article on this work was published in The Ibis in 1869, the journal of which he became Editor (1883-86 and 1895-1900).

However, it was in June 1882 that he undertook to complete Professor Newton’s work of revising the fourth edition of Yarrell’s History of British Birds, first published in 1843.

Saunders was overawed by the high standard of excellence that he perceived in his predecessor’s work and was given just two and a half years to complete the task. He teased over taxonomic orders. Should not terns and gulls follow the closely related sandpipers, or are they so closely related that they should be in the same Order? Opinions, it seemed, varied over the order of petrels, auks, divers and grebes (what’s changed in over 100 years?). He chose to accept prior views.

When the first edition of his own An Illustrated Manual of British Birds was published in 1889, the number of species considered British numbered 367. Saunders also undertook the role of editing and revising the second revised and enlarged edition. This Manual was acclaimed the standard authority on the subject (Ann. Soc. Nat. Hist., Jan 1908). With the addition of Melodious Warbler, Gyr Falcon, Frigate Petrel, Yellow-legged Gull and Black-browed Albatross, to note but a few, the total rose to 384. Today, as this goes to press, British Birds (114: 439, 2021) notes that the British List has increased to 626 with the addition of White-chinned Petrel, Brown Booby, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher and Ruby-crowned Kinglet.

Saunders’ keen interest and focus on the Laridae (gulls, terns and skuas) included his authorship of the major account of this group he produced for volume 25 of the Catalogue of Birds in the British Museum (1896).

Saunders clearly understood the impact of meteorological conditions on migrations and seasonal movements. His task in assimilating the large amount of new data from the Hebrides, Orkneys, local faunas such as The Birds of Devon, and observations at light-houses and light-vessels into the revised book was immense, including all the associated correspondence that this generated.

He attended the very first Club meetings in 1892. With his keen intellect and memory, together with all his experience and knowledge of British birds behind him, he really was the man for the job. Howard was a consummate committee person, being a Fellow not only of the Linnean Society but also of the Royal Geographical Society and the Zoological Society of London. In those early years, attending lectures and meeting people in person was the essential way to collect and disseminate information. Noting this and his appetite for data, as well as his ability to write, it is not surprising that he was a driver behind the formation of the British Ornithologists’ Club and became the first Club Secretary. Abel Chapman described him as ‘a living encyclopædia and that by no means confined to ornithology’. He married and had two daughters, whom he took with Abel on a steamer to Norway in 1897 and pointed out to them the whiter-headed continental form of the Long-tailed Tit peering from a pendant nest. A keen eye and a keen intellect! That was Howard Saunders (1835-1907).

Author Information

Stephen Chapman