An interview with Dale Forbes, lead author of ‘Habitats of Europe’ published by Princeton University Press.

Dale Forbes is a lifelong naturalist and conservationist with an MSc in Biogeography. He works in strategy and marketing at Swarovski Optik, is a member of BirdLife International’s Advisory Board, and is the regional coordinator for eBird in Austria. He loves creating soundscapes that capture the essence of being immersed in nature https://soundcloud.com/capepolly

Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne interviews Dale Forbes. This article was first published in the Quarterly Newsletter (No. 280) of the London Natural History Society.

How did this book come about?

Following the success of Habitats of the World (2021), we have been working on producing guides to each of the world’s regions. These regional (roughly continental) guides are able to cover more habitats and dedicate more space to each of them.

How many years was this book in the making?

Habitats of Europe took about 3.5 years to put together – we spent an extensive period researching the European context. That scientific foundation then needed to be re-written to make it engaging and easy to read. We wanted to create a book that would be easy to turn to any page and discover something fascinating about Europe’s wildlife and nature.

What do you want to achieve with this book?

We have two major aims. The first is to help naturalists see our natural environment from a range of different perspectives. Geology, climate, botany, and wildlife assemblages are all intricately intertwined. At a simple level, by starting to understand how all of this fits together, it is so much easier to find special birds (and other wildlife).

The second aim was to tie it into the larger scientific work that we are pursuing in the background. Habitat mapping is often based on the extrapolation of climate and geology. This is, however, far from accurate. By understanding the associations of wildlife assemblages with habitats, we can use citizen science data to significantly improve both habitat and wildlife distribution maps.

Is there a fun fact or something amazing you learnt during the writing of the book?

For the longest time, I did not feel like I was really getting to grips with why European habitats had the wildlife species assemblages they do. It was only after I started to see the continent through the lens of the Pleistocene, that things started to make sense. So many of our species have evolved (and survived) through tumultuous climate change and alongside megaherbivores. I would have loved to have seen a natural Europe with lions, elephants, rhinos, Irish Elk, and bison, but unfortunately our predecessors got here first. It is phenomenal that Türkiye still had Northern Lions in the late 19th century and Caspian Tigers into the 1990s!

Were there any memorable moments during the course of writing this book?

I was at a Paleo-ecology conference and one of the presenters shared a paper on Pleistocene beech refugia. My head exploded as I realized that these corresponded rather neatly with the distribution of Fire Salamander subspecies. I suspect that these ice age changes in beech distribution drove the diversification of Fire Salamanders and, more specifically, that the distribution of Fire Salamander subspecies could contribute to our understanding of beech refugia and spread through Europe in the Holocene.

Chalk downlands and chalk streams, which are important habitats in the UK are absent in your book. Is this due to constraints of space of because they did not qualify under the criteria for distinctiveness you have set out in the introduction?

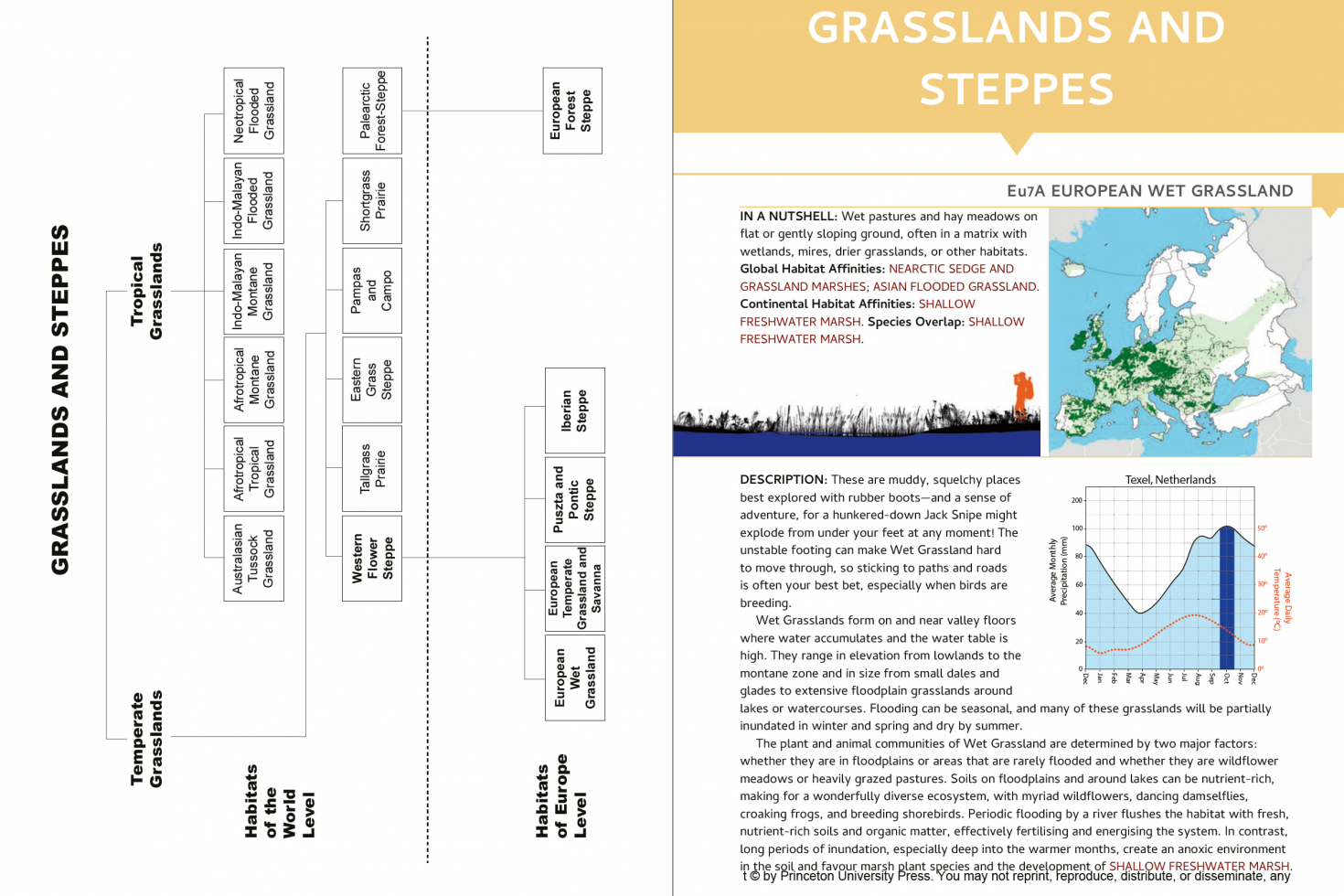

The chalk grasslands and heathlands of southern England have some incredible plant and invertebrate biodiversity, but they are not particularly distinct in their vertebrate assemblages. The Temperate Grassland and Savanna habitat covers a wide range of ecosystems, geology and plant communities – and we debated long and hard about how to deal with this diversity – but ended up leaving them lumped together in order to remain true to the vertebrate-led distinctiveness criteria outlined in the introduction.

For anyone who wishes to pursue this topic more, are there any online resources you would recommend?

Find out more about the various Habitats of the World on our website https://www.habitatsoftheworld.org/. We are continually working on improving it and including more information as we work across the globe and further the science that underpins our guide books. In addition, the European Nature Information System (EUNIS) database maintained by the European Environment Agency (EEA) is an incredible resource on the habitats of Europe. It is a hierarchical classification system which covers all terrestrial, freshwater and marine habitats across Europe. Another good site is FloraVeg.EU. This is an online database of European vegetation, habitats and flora data.