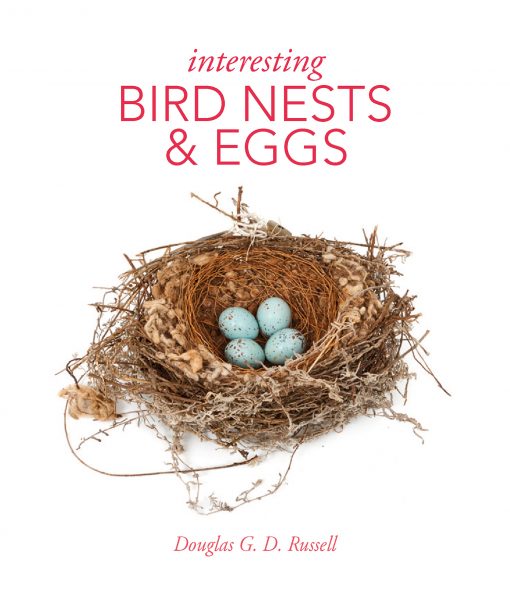

An interview with Douglas Russell, author of ‘Interesting Bird Nests & Eggs’, published by the Natural History Museum.

Douglas G. D. Russell is the Senior Curator responsible for the internationally renowned birds’ egg and nest collections at the Natural History Museum (NHM). After studying Biological Sciences at Edinburgh Napier University, he began his curatorial career at the Royal Museum of Scotland (now National Museum of Scotland) preparing bird specimens from the 1996 Sea Empress oil spill – an environmental catastrophe which resulted in the death of thousands of birds including Common and Velvet Scoters, Guillemots, Red-breasted Mergansers, and Razorbills amongst many others. Curatorial work at both the Natural History Museum and Scarborough Museum followed before taking on a new role leading public engagement in taxonomy and systematics at the NHM. In 2002 he became the sole curator of the world’s largest egg and nest collection as part of a team of bird curators at the Natural History Museum, Tring.

Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne interviews Douglas Russell.

How did this book come about?

The idea for Interesting Nests first formed in the early 2000s – shortly after I started in my role curating the Natural History Museum (NHM) collection of Birds’ eggs and nests. I started working on the format during the pandemic, choosing the specimens, and writing the accounts in 2022. Part of the reason the book took so long to see the light of day was the time needed to re-curate the entire NHM nest collection to a modern taxonomy. The Howard & Moore 4th Ed. Checklist recognises 236 separate families – a dramatic increase in comparison to earlier global taxonomies. Nests are often inherently fragile, and the collection has experienced a greater degree of loss than any other area of the NHM vertebrate collections. Thousands of nests have deteriorated and been lost over the last 200 years sadly. What remains is what has survived, not what was in the collection originally. This made the stabilisation of the remaining specimens the priority but also gave me huge opportunity to think about what specimens might tell a distinctive story about each species at that place and time – as well as illustrating the scope and history of the collection.

What do you want to achieve with this book?

I wanted to illustrate at least one nest for each bird family we had examples of within the NHM collection. This ended up being around 120 families. It is obviously a biased list as I was limited to what we had in the collections. Nest collections inevitably have strong collector bias – they are limited to what the collector found, could access and ultimately what could be transported. Consequently, large bulky, inaccessible nests are rare. Some nests are just samples of part of the nest or lining, e.g. burrow nests in which the burrow itself is almost impossible to preserve. I also wanted to try and show nests from around the world. I was able to choose specimens from Africa, the Americas, Antarctica, Asia, Australia/Oceania, and, of course, Europe. I also wanted to show the oldest surviving specimens alongside some of the most recently acquired. Birds are arguably often at heightened risk during breeding, so lastly I wanted to draw the reader’s attention to conservation issues globally, including those species we have tragically already lost (e.g. the nest of the extinct Stephens Island Piopio in New Zealand) and those on the brink of extinction (e.g. Liben Lark in Ethiopia).

Is there a fun fact or something amazing you learnt during the writing of the book?

I learnt a lot from the process and thoroughly enjoyed the opportunity to research each family and species. The Blue-capped Ifrita Ifrita kowaldi is one of the few birds which demonstrably has batrachotoxin in its skin and feathers, acquired from its diet of poisonous beetles. This powerful neurotoxin causes numbness, tingling, irritation, and potentially paralysis or worse and this makes their nests one of the few known potentially protected by poison. Another exciting opportunity was the realisation that the nest of the Long-tailed Fantail Rhipidura opistherythra that we held in the NHM collection had never been formally described since it was collected in 1901.

Were there any memorable moments during the course of writing this book?

Yes absolutely – trying to work out with Jonathon Jackson the photographer exactly which way some nests were orientated in life was sometimes challenging! Nests – especially those collected nearly 200 years ago – are sometimes distorted and look very different to how they might have looked when built. I was really excited to find the exact nest of Albert’s Lyrebird Menura alberti sent to John Gould in London in the mid-1800s. We had to use an 1853 illustration to try and work out how it once looked since it had been squashed beyond recognition in the 170 or so years since it was found!

For anyone who wishes to pursue this topic more, are there any online resources you would recommend?

Cornell Labs – Birds of the World continues to be an extraordinary online resource available via subscription. I would also highly recommend the Biodiversity Heritage Library as a free, incredible resource of historical literature; from James Rennie’s Architecture of Birds (1831) to many relevant and articles in the Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club – there is centuries of fascinating articles and books on nests and eggs in there for anyone to freely peruse!