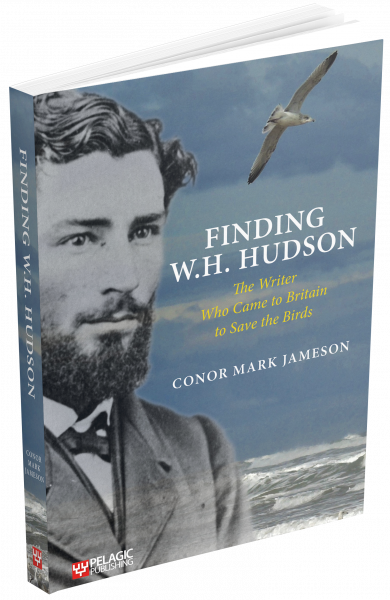

An interview with Conor Mark Jameson on his book ‘Finding W.H. Hudson: The Writer Who Came to Britain to Save the Birds’ published by Pelagic Publishing.

Reproduced with permission from the Quarterly Newsletter (Issue No. 272, March 2024) of the London Natural History Society.

Conor Mark Jameson has written for the Guardian, BBC Wildlife, the Ecologist, New Statesman, Africa Geographic, NZ Wilderness, British Birds, Birdwatch and Birdwatching magazines and has been a scriptwriter for the BBC Natural History Unit. He is a columnist and feature writer for the RSPB magazine and has worked in conservation for 20 years, in the UK and abroad. He is the author of Silent Spring Revisited, Shrewdunnit and Looking for the Goshawk.

How did this book come about?

For most of the 25 years that I worked for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), at The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, W.H. Hudson was just ‘the man above the fireplace’, looking back at the world from a painting: pensive, mute. Then I got to know him better.

A story told by Hudson in his 1901 book Birds and Man captured my imagination. He describes staying in a big house one night, sitting by a fireplace, as a storm raged. He fell asleep and had a nightmare that when he died he would be stuffed by the taxidermists of hell, like so much of the wildlife he loved, and condemned to eternity with no voice. And it struck me that here he is today, beside a fireplace, voiceless. A mission began to give him back his voice, to reanimate him. The more I found out about Hudson, the more perplexed I became that he had faded into obscurity. This has felt like a process of restoration. I have been particularly interested in piecing together the story of his work and relationships with the other early pioneers of conservation after he came to Britain age nearly 33, from his letters, which is an untold story. I’ve enjoyed bringing what I know of natural history, campaigning and communicating science to the public to this task.

How many years was this book in the making?

When I found out that a sanctuary and monument to Hudson was created in Hyde Park after his death in 1922, I made my first pilgrimage to it in May 2011. I can place the date because it was the day that Barcelona came to London for the European Champions League final in men’s club football, inspired by another genius from the Argentine – Lionel Messi. There was a festival of football in Hyde Park as part of that occasion. I could see the huge, silver trophy glinting in the sun, and huge crowds queuing just to touch and be photographed with it. I might have been distracted by this other grail, but I kept my eye on my prize, feeling a bit like an intrepid explorer, without even a map to guide me (the tourist info kiosk was unable to help). My biography of Hudson has been gestating since then.

What do you want to achieve with this book?

I have a sense of discharging a debt, to the memory of Hudson and his friends, in particular the women who founded modern conservation campaigning, who turned wildlife from something to be owned and exhibited into something to be nurtured and protected. Their story is moving and inspiring.

Is there a fun fact or something amazing you learnt during the writing of the book?

There have been many revelations. From a London point of view, I discovered that the Bird Society as he called it – what we know as the RSPB today – first met in Notting Hill. Croydon meetings were a year or two later. It is well known I hope that simultaneously Emily Williamson was convening her group in Manchester. I think London residents may be astonished at his efforts for the city’s green spaces – he almost talked himself into court on more than one occasion. He spearheaded a campaign to save a big chunk of Kew – but no spoilers!

I have also been amazed by the famous names that Hudson knew, and the awe in which they all seem to have held him. And all this despite the social anxiety that he never fully overcame and his preference for spending time alone in nature, or in the humble homes of everyday rural folks.

Were there any memorable moments during the course of writing this book?

Visiting Argentina and Hudson’s natal home stands out, as does giving a talk in the village in Wiltshire where he wrote his classic Shepherd’s Life. Being absorbed in Hudson’s largely unseen letters was like sifting for precious gems and provided many ‘eureka’ moments. Inhabiting another life, in another time and place, is intense, and a little haunting. It has been a very diverting experience.

For anyone who wishes to pursue this topic more, are there any resources you would recommend?

I hope that the book stimulates more interest in this, not least because I have so few people to talk to about it in any level of detail!

I’d point people to Hudson’s books, of course, the text of many which are online, and earlier biographies, especially Ruth Tomalin (1982). Also, Tessa Boase’s Etta Lemon which weaves together the story of the plumage campaign with the campaign for votes for women. Only some propertied men had voting rights until 1918. Societal change rarely happens quickly, and the rights of people, animals and nature have had to be fought for bravely. I think it’s important to recognise and remember this, and to heed the lessons of history.